Forgiveness and Remembering

In search of the meaningful homily. What’s in a word?

Deacon Tim Healy Comments Off on Forgiveness and Remembering

“What’s he talking about?”

“He doesn’t say.”

Have you ever overheard this conversation between parishioners after your homily? There hasn’t been a deacon who hasn’t heard something like it, or perhaps similarly heartwarming sentiments expressed about the prevalence of poor homilies. Mindful of that, the authors of the new National Directory for the Formation, Ministry, and Life of Permanent Deacons highlight the importance of preparation and practice in preaching.

We can make our homilies better by drawing attention to the meaning and structure of the words of Scripture themselves, with an eye toward conveying their deeper meanings. What deacons bring to this level of engagement is our unique ability to absorb the profound and relate it to people’s everyday lives in simple, meaningful and delightful ways that illuminate the richness of liturgical seasons.

“Forgiveness” and “remembering” are standard fare for homilies and workshops throughout the liturgical year. It can be challenging to come up with fresh approaches to present them to people. Everyone already knows what these terms mean, don’t they? Maybe, maybe not. Using the structure and meaning of these words themselves can take us someplace new, and allow us to experience them in unique ways. This approach might sound like tedium incarnate, and it will be if you simply explain the words and stop there. But we’re deacons, and we’re creative, so read all the way to the end and be amazed!

A Word about Words

Exploring a word’s structure and history frequently reveals much deeper meanings for it than are suggested simply by its dictionary definition. Beyond that, when we let our imagination run free to explore other connections and parallels for words, the way poets and other creative writers do, we can find ourselves at the doorstep of insights far beyond the self-evident.

In addition to insights gained by inspecting a word’s components, it’s helpful to become aware of the ways in which some words can be used in different though related ways. For example, many of us learned in formation that the Hebrew word rûaħ means “wind” at one level, “breath” at another and “spirit” at yet another. It’s not that anyone’s confused about how to express what’s meant, but rather that we’re letting the language we use to illustrate different levels of meaning. All of the meanings are present simultaneously.

Forgiveness and Remembering

Let’s take a look now at the words “forgiveness” and “remembering” in that light.

Our word “forgiven” comes from the Anglo-Saxon verb forġiefan. The word meant “to give, grant, allow, remit or pardon.” Although that remains its most obvious meaning today, the prefix “for-“ has multiple meanings. One of the more significant is “preceding in time, or before.” The suffix, “-ġiefan,” means “to give.” Putting the two together links the notions of something that happened in the past and something that has been given.

Maybe, like me, you’ve wondered how this term came to mean what it does. Exactly what had been given in the past, and how did that correspond to the action of pardoning someone in the present?

What has always been given in human and divine relationships is love, in one or more of its many manifestations. To forgive is to restore a love that has always been present.

We can get a visceral sense of this original love by finding a baby picture of ourselves or someone else we love and using it as an icon. As we contemplate this icon, we’re peering at ourselves at the dawn of our creation, as the delightful, unique expressions of God’s love that we are, created simply to love and be loved. We’re looking at ourselves as we appeared before anything ever happened to occlude that love; before we’d been disciplined, graded, complimented or criticized.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

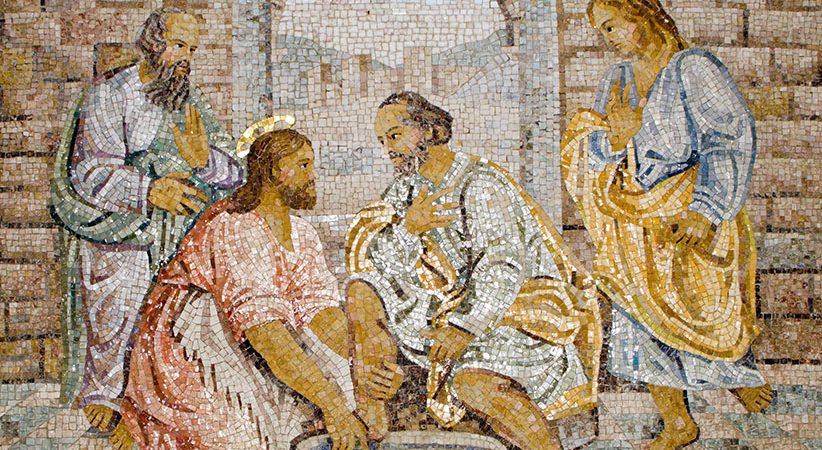

WELCOME OF THE PRODIGAL SON

“Dear Friends, how is it possible not to open our hearts to the certainty that in spite of being sinners we are loved by God? He never tires of coming to meet us, he is always the first to set out on the path that separates us from him.”

— Pope Benedict XVI, Angelus address, Sept. 12, 2010

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Now consider Luke’s lovely story of the prodigal son in Chapter 15 of his Gospel. Recall that the prodigal’s father had always been on the lookout for him, ran to greet him when he saw him, and immediately restored him to his former position in the family. The father’s love for his son had always been there. The bonds of love had been broken, certainly, but the love itself had never vanished. All the son had to do was to decide to acknowledge his error and return to his father, just as we are encouraged to do. Giving new meaning to the word “immediately,” his father fully restored the bond that had been severed even before his son had finished apologizing.

Let’s take a look at the other word now — “remember.” The prefix “re-” means to do something once more or to repeat. Etymologically speaking, the suffix “-member” just means “to call to mind.” Combining the two yields our familiar usage. Etymology though doesn’t have the last word when it comes to meaning.

Reconciliation

Let’s take some poetic license here, à la “ruah,” and notice that that the suffix “-member” can also be used to refer to a body part, like an arm or an eye. Considered this way, the opposite of “to remember” would be not “to forget,” but “to dismember.” To “re-member” in this sense then is to restore to wholeness what had been torn asunder. This is the love-driven meaning that lies at the heart of reconciliation.

Using Luke again, consider Chapter 23 and the story of the good thief. After acknowledging, as did the prodigal son, that he had led a bad life, he asks Jesus to “remember” him when he comes into his kingdom. Jesus tells him immediately that he will be with him in Paradise that day.

The thief had not asked Jesus to call him to mind and think happy thoughts about him from time to time; it’s much more than that. The man who had cut himself off from the love of God, who had dis-membered himself from his fellow humans, was asking to be re-membered, or reconnected to it. Of course, Jesus grants him his request — it’s what his mission is all about after all, as the word “religion” (“re”: “about”; “ligio”: “connection”) clearly tells us.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Remembering the Good Thief

Pope Francis spoke of the repentance of the “good thief” in his general audience on Sept. 28, 2016. He said: “The good thief … addresses Jesus directly, invoking his help: ‘Jesus, remember me when you come in your kingly power’ (Lk 23:42). He calls him by name, ‘Jesus,’ with confidence, and thus confesses what that name means: ‘the Lord saves’: this is what the name ‘Jesus’ means. That man asks Jesus to remember him. There is so much tenderness in this expression, so much humanity! It is the need of the human being not to be forsaken; that God may be always near. In this way a man condemned to death becomes an example, a model for a man, for a Christian who trusts in Jesus; and also a model of the Church who invokes the Lord so often in the liturgy, saying: ‘Remember … Remember your love.’”

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Ask yourself if the sting of betrayal, rejection or abuse is not at its core the sting of love betrayed, rejected or abused. Beyond mere pardon, remission of punishment or exculpation, is not the goal of extending forgiveness to those who honestly and completely acknowledge the evil they have done to restore the broken bonds of trust, acceptance and affection that were originally manifested in that love?

Is not the wholeness that forgiveness provides at the root of the wholeness with which God asks us to love God, ourselves and others? It’s much, much more than simply being let off the hook.

The Lenten season we just experienced provides the opportunity for us to allow God’s forgiveness to reconnect what has been dismembered by us when we’ve forgotten our origin, our destiny and the permanence of love.

What’s really in a word? Everything. Let’s tell people.

DEACON TIM HEALY is a deacon for the Archdiocese of Hartford and conducts retreats on forgiveness. He is the author of “Tales for the Masses” (CSS, $16.95) and the upcoming “More Tales for the Masses.”