Preaching Advent

Connecting the dots within the rhythm of the liturgy

Deacon Steven D. Greydanus Comments Off on Preaching Advent

G.K. Chesterton begins “The Everlasting Man” with a parable inspired by England’s immense chalk hill figures, like the White Horses of Uffington and Westbury. He imagines a boy growing up on a slope bearing the image of some gigantic figure, unaware that the familiar borders of his farm and garden are small parts of a vast, unguessed design. One day he goes in search of the mysterious monument of the giant he has heard about, and, of course, it’s not until he has gotten far enough from home that he is able to see the whole picture.

Something like this applies to how many Catholics experience the liturgical calendar and the Lectionary.

We’re all attuned to the rhythms of the workweek. While we may occasionally be surprised that it’s already (or only) Wednesday, the arrival of the Lord’s Day seldom if ever catches us unawares. But we all know Catholics who are surprised every year by the capricious arrival of Ash Wednesday; and I remember well, year after year as a young Catholic convert, the startled feeling that once again the solemnity of Christ the King at the end of the liturgical year had come upon me like a thief in the night.

As for the Lectionary, it remains terra incognita to most Catholics, no matter how many times they’ve heard the same triennial cycle of readings. Those who are paying attention on any given Sunday may note thematic links between the first reading and the Gospel — but who recalls last Sunday’s readings well enough to recognize, for example, a string of kingdom parables or readings from the Sermon on the Mount, let alone to follow St. Paul’s line of thought over a number of weeks?

Liturgical Context

The homily is meant to flow from and serve the liturgy. One way to pursue this goal is to work to help parishioners grasp and appreciate the liturgical big picture: the pattern of this Sunday in relation to last Sunday, next Sunday, and the larger seasonal landscape; to stitch back together the biblical texts parceled out in the Lectionary.

The solemnity of Christ the King marks, of course, the last Sunday of the liturgical year, and the new year begins with the start of Advent. In that sense, there is a break, a disjunction. Ordinary Time of Year B ends, and Advent of Year C begins.

But there is also, unnoticed by many, continuity and transition. The eschatological themes of the solemnity of Our Lord Jesus Christ, King of the Universe — apocalyptic trial and tribulation, the Second Coming, final judgment — are foreshadowed on the Sunday before (the Thirty-third Sunday in Ordinary Time) and carry over into Advent.

Especially at the start, Advent has a double focus on both of Christ’s comings, with initial emphasis on looking forward to the Second Coming leading into anticipation of the Christmas celebration of his first coming.

By the Second and Third Sundays of Advent, this double focus converges in the figure of St. John the Baptist. As the forerunner of Jesus and the last prophet of the Old Covenant, John sums up the whole history of Israel’s long expectation of the coming Messiah; as the proclaimer of the imminent kingdom of God, he already points to Christ’s Second Coming.

On the First Sunday of Advent, though, Jesus’ two comings appear as separate themes, with the emphasis on the second, particularly in the Gospel, carried over from the last weeks of the old year.

Three Apocalyptic Weeks

This year, for example, on Nov. 14, the Thirty-third Sunday in Ordinary Time, the Gospel is from St. Mark’s “Little Apocalypse,” with a warning of tribulation and a prophecy of the Second Coming, the day and hour of which no one knows. The first reading, from Daniel 12, is likewise a prophecy of worldwide distress culminating the resurrections of the just and the unjust, while the second reading, from Hebrews 10, speaks of how Jesus, seated at the Father’s right hand, “waits until his enemies are made his footstool.”

These eschatological themes anticipate the “crowning of the liturgical year” — as Popes Benedict and Francis have both called the solemnity of Christ the King — in which we look forward to the culmination of history and the definitive revelation of the reign of God. There’s no reason this solemnity should come upon anyone like a thief — not, at least, if we homilists are doing our job!

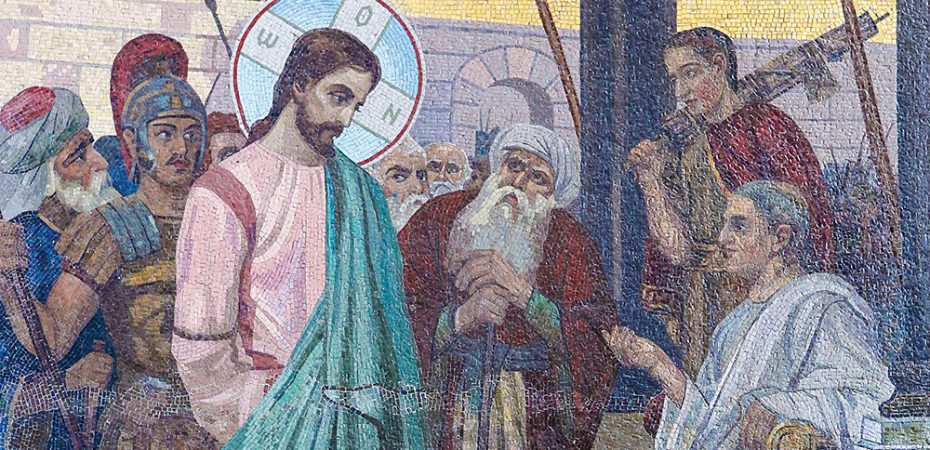

This year, the Gospel for Christ the King is from Jesus’ exchange with Pilate in John 18, with the words, “My kingdom does not belong to this world.” The first reading is, again, from Daniel, this time from chapter 7, with the Son of man coming on the clouds of heaven and receiving everlasting dominion — language echoed in the second reading from Revelation 1 (“Behold, he is coming amid the clouds”).

Then comes Advent: the sanctuary decked in violet; the familiar strains of “O Come, O Come, Emmanuel”; and the first reading from Jeremiah 33: “In those days, in that time, I will raise up for David a just shoot.” All this invites us to turn our minds toward anticipating the celebration of Christ’s birth.

Perhaps the second reading from 1 Thessalonians, with Paul’s concern for his readers to be blameless at the Lord’s coming, slips by without much notice. But then, with the faithful standing for the Gospel, comes yet another eschatological warning, this time from Luke’s “Little Apocalypse”: signs in the heavens, people dying of fright, and the Son of Man “coming in a cloud with power and great glory.”

If this apocalypticism feels like an intrusion or anomaly in our Advent celebration, we homilists haven’t done our job. Or, at least, we have our work cut out for us!

Making Everything Count

A complicating factor for most deacons is, of course, limitations on our preaching opportunities. I know deacons who preach on a weekly basis, but once a month or so is more the norm. We must make the most of what is given us.

If we preach Christ the King or the Sunday before, we can look forward toward Advent and connect the dots ahead of time. If we’re on for the First Sunday of Advent, we can pick up the strands from the previous Sundays, perhaps recalling themes from prior homilies, whoever preached them.

A homiletic series with running themes is no bad thing, even with more than one homilist preaching. If one’s relationship with one’s pastor and/or other celebrants allows for advance collaboration, so much the better.

DEACON STEVEN D. GREYDANUS writes for the National Catholic Register and has contributed to the New Catholic Encyclopedia and the Encyclopedia of Catholic Social Thought, Social Science, and Social Policy. He has M.A.s in religious studies and theology from, respectively, St. Charles Borromeo Seminary and Immaculate Conception Seminary at Seton Hall University.